Yitro reminds us that burnout is a perennial problem.

Over the last few months, I’ve been reflecting on the idea of capacity, burnout, and self-care. These ideas have come to the forefront in our society in the last year, in the face of the pandemic, but have been with us forever. With little to no distinction between work life and home life, the unending stream of Zoom meetings, the inability to relax due to the wild political circumstances, and the separation from friends and family.

Our capacity, as individuals, is limited.

We only have twenty-four hours in a day, a third of it sleeping (hopefully).

We only have seven days in a week, some of which is Shabbat or holidays.

We only have fifty-two weeks in a year, most of which we’re working or obligated.

Time is our most valuable resource and we fill it, myself included, with so many things that drain us of our vitality. The hours I’ve spent staring at my phone watching television as a break from staring at my phone doing email in between staring at my computer trying to work and teach.

This limited capacity is further impacted by our awareness of our personal vision, of our passions, the things that revitalize us.

How often have you asked yourself, “Is this how I should be spending my time?” or grumbled, “I’m spending my time with this when I could be doing something that fulfills me!”

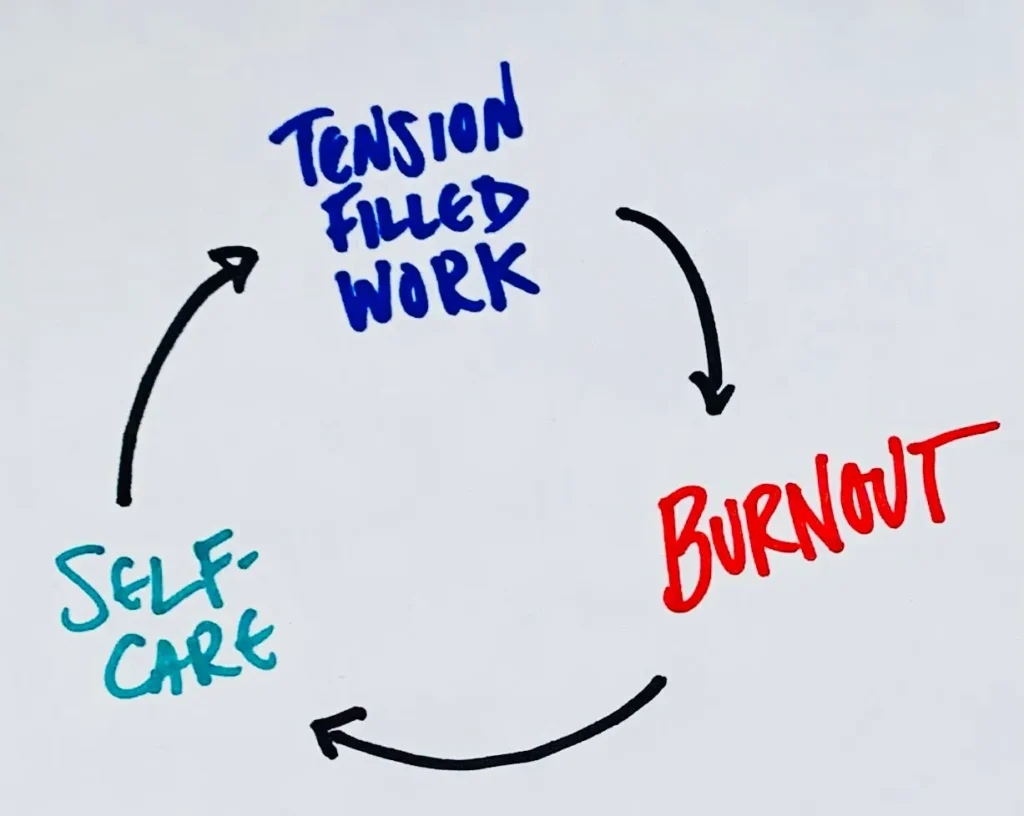

This tension, this grinding together of what we’re called to do, driven to do, and how we actually spend our time, is what leads to burnout. I’m not talking about the desire to go on a hike instead of work or reading a book instead of meeting with clients. Instead, the parts of our jobs that fulfill us with the things that feel like a waste of time. The meetings that could be emails, for example.

This burnout, the pure exhaustion, is what so many of us feel at this time.

And the way we respond to it matters and there are only two choices. One, we can do self-care, and two, we can deal with the tension building activities.

Let me define terms here for a moment. Self-care is the activities we do that recharge us that are outside of our work. For some it’s knitting, watching tv, hiking, reading a book, taking a bath, or a million other things. This is all well and good, but for one thing:

Self-care is vacation.

I love a good vacation and vacations are important, but their efficacy only lasts a few days. In the APA study, it says:

“Nearly a quarter of working adults (24 percent) say the positive effects of vacation time — such as more energy and feeling less stress — disappear immediately upon returning to work, the survey found. Forty percent said the benefits last only a few days…

The majority of working Americans reported positive effects of taking vacation time and said when they return to work their mood is more positive (68 percent) and they have more energy (66 percent) and motivation (57 percent) and feel less stressed (57 percent). Additionally, working adults reported that, following time off, they were more productive (58 percent) and their work quality was better (55 percent).”

So, vacation is good, it makes us feel less stressed, but it doesn’t really last very long. This dynamic is really important and we need to understand it in order to think about how we deal with our problems.

The other choice is dealing with the tension-building activities.

And this is where I want to bring in this week’s portion, Yitro.

This portion brings us to one of my favorite interactions in the whole Torah. Yitro, Moses’ father-in-law, sees how much Moses was doing and sees that it is burning him out.

But when Moses’ father-in-law saw how much he had to do for the people, he said, “What is this thing that you are doing to the people? Why do you act alone, while all the people stand about you from morning until evening?”

Moses! You’re doing too much of the job on your own!

Moses replied to his father-in-law, “It is because the people come to me to inquire of God. When they have a dispute, it comes before me, and I decide between one person and another, and I make known the laws and teachings of God.”

He responds to his father-in-law that the task is uniquely his. He’s the conduit to God at this moment in time and the people need him! He’s the one who is implementing God’s laws for the people.

But Moses’ father-in-law said to him, “The thing you are doing is not right; you will surely wear yourself out, and these people as well. For the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone. Now listen to me. I will give you counsel, and God be with you! You represent the people before God: you bring the disputes before God, and enjoin upon them the laws and the teachings, and make known to them the way they are to go and the practices they are to follow.

Yitro then explains burnout to his son-in-law. You can’t do it all yourself. It isn’t possible. “You will surely wear yourself out.” While the science on burnout is still a burgeoning field, we have known for millennia that we have to take care of our ability to actually do the job before us.

So Yitro offers great advice, build for yourself a team:

You shall also seek out from among all the people capable men who fear God, trustworthy men who spurn ill-gotten gain. Set these over them as chiefs of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens, and let them judge the people at all times. Have them bring every major dispute to you, but let them decide every minor dispute themselves. Make it easier for yourself by letting them share the burden with you. If you do this—and God so commands you—you will be able to bear up; and all these people too will go home unwearied.”

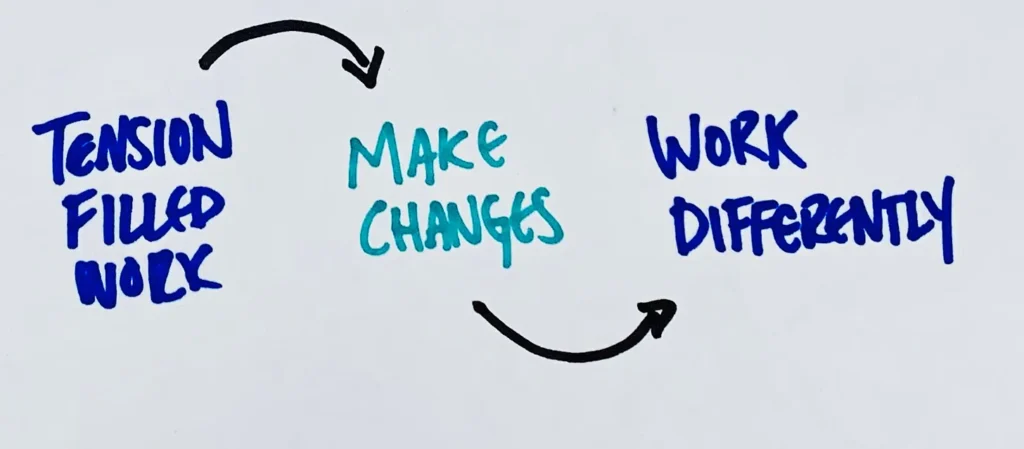

Now, putting aside the patriarchal nature of his response and reinterpreting it for our context: create a team for yourself. No one is meant to do all the work alone. Find a different way to solve the problem.

Burnout cannot be solved with self-care.

It is a stop-gap measure to recharge us for a limited amount of time before becoming burned out again. Instead of solving his burnout with self-care (which, again, has value), Yitro guides Moses to solve the source of the problem, his limited capacity. Let’s imagine that Moses was taking vacation days, or even Shabbat, off. When he got back, the situation hasn’t fundamentally changed.

We can improve our capacity by delegating, outsourcing, or limiting the tasks we take on. Here, we can learn the lesson from Yitro and Moses:

Moses chose capable men out of all Israel, and appointed them heads over the people—chiefs of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens; and they judged the people at all times: the difficult matters they would bring to Moses, and all the minor matters they would decide themselves.

Moses can take on the most challenging roles, perhaps the ones that revitalize him and delegate the rest to trusted folks.

Now, I recognize delegating our work isn’t possible for everyone. But I believe that each of us can find ways to reduce the friction in our jobs that reduce our capacity and increase the likelihood of burnout. This is a perennial challenge for all of us.

Yitro, Moses, and the APA study all led me to realize that we have to think differently about how we spend our time.

I’ve made these diagrams to clarify my thinking.

Yitro is teaching Moses, and us, that we need to be seriously reflective of how we spend our time and what we do when we face burnout.

How do you deal with burnout?