October 15, 2020

What we can learn from the (re)creation of the universe

Once again, we’ve reached the beginning of the story. Bereshit, “in the beginning!” Though, if we’re going to get technical, the first word makes no sense and should probably be translated as “in the beginning of.” But nonetheless, the beginning!

Every year we find ourselves exactly here. Sort of at the beginning and also in the middle. For us, as we restart the Torah, we are in the middle of our lives. So while we are reading the book from the beginning, we carry all of ourselves along with it. I’d argue that’s a good thing. That’s the nature of perspective, our own experience filtering everything we experience.

This week we’re going to look at a midrash. Midrashim are early rabbinic explorations of Jewish ideas based on the text of the Torah. Rabbinic fan fiction, if you will. The Torah usually speaks in the language of actions and rarely describes what the characters are thinking. It happens, but rarely.

When God created the universe, what was God thinking? What was God imagining would happen? What did God want to happen?

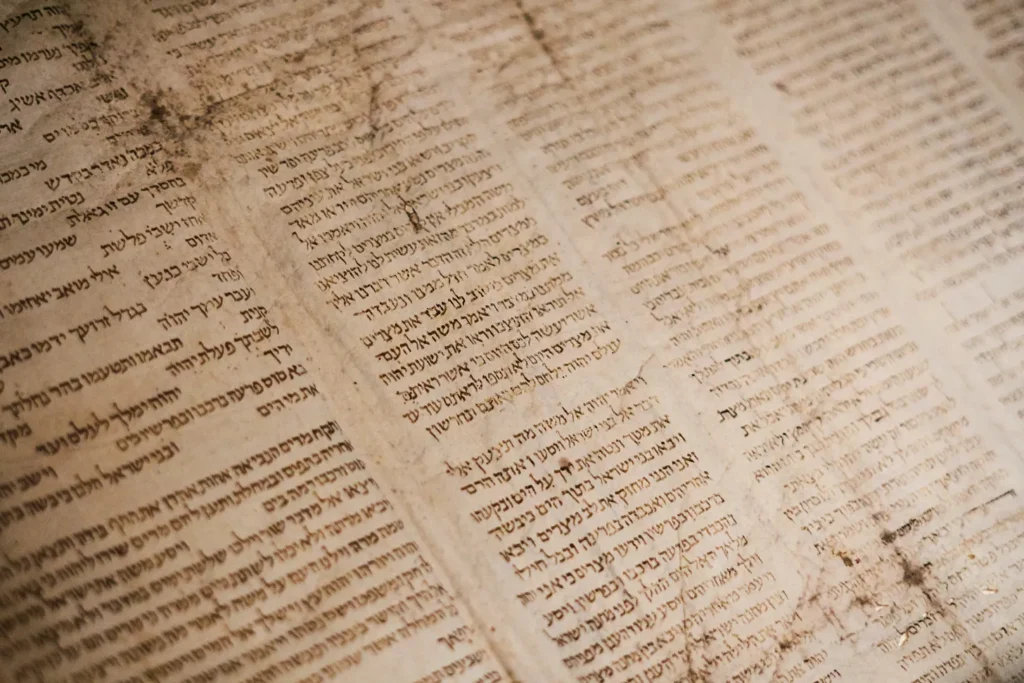

Every letter is an invitation to interpret, imagine, and explore a new idea.

Classically, Rashi, the 11th-century French commentator, says this about the first verse in the Torah:

בראשית ברא אֵין הַמִּקְרָא הַזֶּה אוֹמֵר אֶלָּא דָּרְשֵׁנִי

In the beginning [God] created This verse only calls out, ‘interpret me.’

According to Rashi, for good reason, the verse is pleading to be interpreted! What a strong way to get started.

Later in the chapter, as the creation is getting underway, we notice that at the end of each day, it says, וַֽיְהִי־עֶ֥רֶב, and it was evening. The midrash is going to focus on that “and” and bring our attention to why that might be there.

This is the midrash, from Bereshit Rabbah:

מַר רַבִּי יְהוּדָה בַּר סִימוֹן, יְהִי עֶרֶב אֵין כְּתִיב כָּאן, אֶלָּא וַיְהִי עֶרֶב, מִכָּאן שֶׁהָיָה סֵדֶר זְמַנִּים קֹדֶם לָכֵן.

Rabbi Yehudah bar Simon said [about the verse]: it does not say, ‘It was evening,’ but [rather] ‘And it was evening.’ From here we can derive that there was a time-system prior to this.

Let’s just pause there for a moment. WHOA, so much is packed into a single vav.

Because the verse includes the word, “and” we can infer that there was something that had come before our system of evenings and mornings. What a radical idea! If I had said, “and I ate a sandwich” you might reasonably wonder, what did I have before the sandwich?

It is this close reading of the text that Rashi is encouraging of us. Of course, the midrash continues:

אָמַר רַבִּי אַבָּהוּ מְלַמֵּד שֶׁהָיָה בּוֹרֵא עוֹלָמוֹת וּמַחֲרִיבָן, עַד שֶׁבָּרָא אֶת אֵלּוּ, אָמַר דֵּין הַנְיָן לִי, יַתְהוֹן לָא הַנְיָן לִי. אָמַר רַבִּי פִּנְחָס טַעְמֵיהּ דְּרַבִּי אַבָּהוּ (בראשית א, לא): וַיַּרְא אֱלֹהִים אֶת כָּל אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה וְהִנֵּה טוֹב מְאֹד, דֵּין הַנְיָין לִי יַתְהוֹן לָא הַנְיָין לִי.

Rabbi Abbahu said: This teaches us that God created worlds and destroyed them, until God created these [our universe], saying, ‘This one pleases me; those did not please me.’

Rabbi Pinhas said, Rabbi Abbahu’s reasoning comes from the verse, ‘And God saw all that God had made, and behold it was very good,’ as if to say, ‘This one pleases me, those others did not please me.’

So what happened before “and it was evening?” God created and destroyed many worlds. According to the midrash, it wasn’t that God created our universe and that was it. God was crafting and creating, exploring different versions and models, and imagining and forming from different angles. God was practicing, perhaps. And our universe, for one reason or another, is where God decided that it was good enough to stop. That it “pleased” God and was good.

I think there are three important takeaways from this midrash.

Never stop trying and creating.

As humans, we learn by testing and experimenting. Our curiosity defines us, especially if you watch every science fiction movie about humans. Our never-ending desire to understand, to create new things is a species-wide phenomenon and we’re a part of that. We fail (or decide the universe doesn’t please us, if we’re God) and so we keep at it again and again.

We create universes.

Each universe the Divine created was a different perspective, with its own rules and reality. If not, then why make more than one? As we imagine different things, we create universes in our minds. One’s in which we said something different, wrote more eloquently, and made different choices. Those alternate realities teach us something every time. Now, we’re not God and we cannot change the universe by sheer will, but we can still learn.

Reflect and decide it is good.

We don’t know exactly why God decided this universe was good or good enough. There might have been some incomprehensible measurement system that the Divine was using. Or, possibly, God decided it was good. Intentionally. This would be a reminder that we too can decide something is good. I’m not talking about lying to ourselves. No matter how many times I try a martini, I can’t convince myself it’s good. (You can enjoy it all you want.) But in the end, when we reflect on what we have, what we’ve done, we can say, “this is good and I’ve learned something to make me who I am today.” That has incredible value.

So, on this first week of the Torah, this new beginning that is also in the middle, we can take the time to reflect on where we are in that creation. How we can take moments to create and be created, to choose and be chosen, and to test and be tested. We don’t have to forget everything we’ve learned, we’re in the middle of our individual stories, but we’re at a new beginning. A fresh start.