Whether or not to follow through begins at one exact moment and in no others.

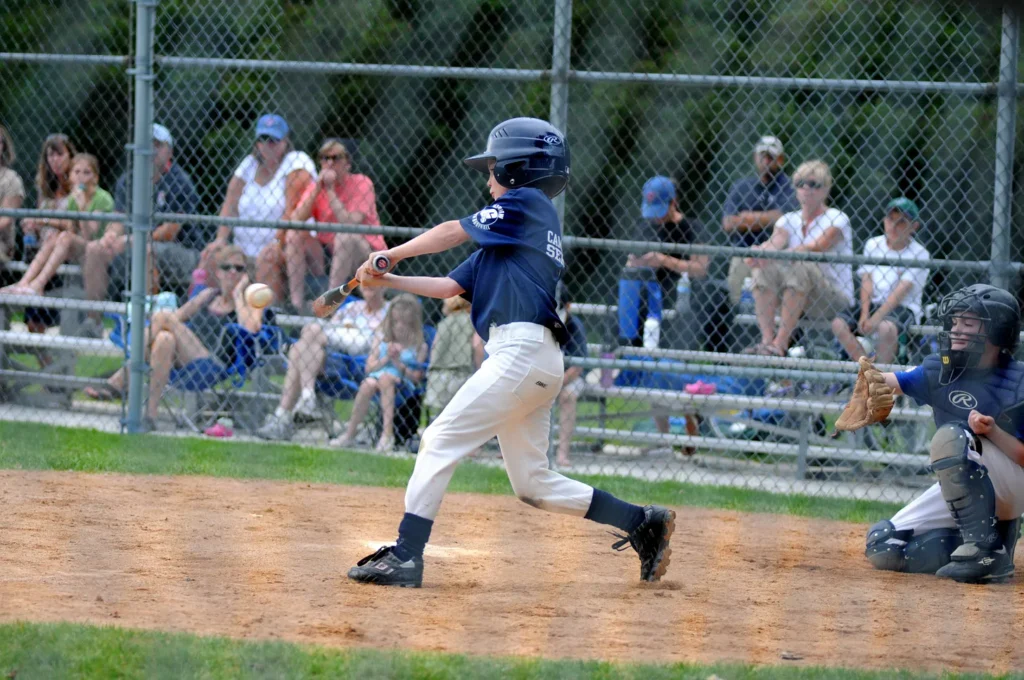

When I was a kid and played in little league, the name for children’s baseball, we learned about the need to follow through. When we swung the bat, it was better to keep swinging until the bat had gone all the way around our body. This technique shows up a lot in various sports, like golf and basketball (and I’m sure many others).

This concept of “follow through” is a fascinating idea.

In the dictionary and in the sports examples above, it is the action of completing something that you’ve started. That’s how we use it colloquially too. I’ve started something and now I have to follow through. Following through is one of the most important “soft skills” we learn throughout our lives.

But if pull apart the two words, follow and through, we can delve a bit deeper. What exactly is being followed? Who is doing the following? If we’re completing an action, what does through refer to?

Whether or not to follow through begins at one exact moment and in no others.

That is, you’ve already begun, you’ve faced an obstacle, and you’re at a decision point of whether or not to push through.

In baseball, the moment is when the ball touches the bat, in golf, when the club hits the ball, and in basketball, when the ball has left your hands. In our daily lives, when we’re faced with a situation when our reactions to a challenge will change the outcome.

In our weekly Torah portion, Sarah dies in the first line. Her life, measured in years is an outlier, given more respect than most women receive in our scriptural tradition. Abraham falls apart, mourning and crying.

He turned to his neighbors and asks (Bereshit 23:4-6):

גֵּר־וְתוֹשָׁ֥ב אָנֹכִ֖י עִמָּכֶ֑ם תְּנ֨וּ לִ֤י אֲחֻזַּת־קֶ֙בֶר֙ עִמָּכֶ֔ם וְאֶקְבְּרָ֥ה מֵתִ֖י מִלְּפָנָֽי׃ וַיַּעֲנ֧וּ בְנֵי־חֵ֛ת אֶת־אַבְרָהָ֖ם לֵאמֹ֥ר לֽוֹ׃ שְׁמָעֵ֣נוּ ׀ אֲדֹנִ֗י נְשִׂ֨יא אֱלֹהִ֤ים אַתָּה֙ בְּתוֹכֵ֔נוּ בְּמִבְחַ֣ר קְבָרֵ֔ינוּ קְבֹ֖ר אֶת־מֵתֶ֑ךָ אִ֣ישׁ מִמֶּ֔נּוּ אֶת־קִבְר֛וֹ לֹֽא־יִכְלֶ֥ה מִמְּךָ֖ מִקְּבֹ֥ר מֵתֶֽךָ׃

“I am a resident alien among you; sell me a burial site among you, that I may remove my dead for burial.” And the Hittites replied to Abraham, saying to him, “Hear us, my lord: you are the elect of God among us. Bury your dead in the choicest of our burial places; none of us will withhold his burial place from you for burying your dead.”

He asks for kindness and they oblige.

A heartwarming moment for sure. But then this strange interaction takes place.

Abraham asks those gathered to intercede on his behalf to this individual Ephron son of Zohar. Why him? It’s not entirely clear. But, it just so happens, he’s standing right there! How lucky! There’s some haggling that takes place, Abraham wants to pay for it, they want to give it to him for free. They land on some price and then Abraham goes to bury his wife.

Why Ephron? Why so much back and forth of payment? Why would the Hittites need to intercede? Did Abraham not see him in the crowd? There are so many questions.

There are two perspectives on who this Ephron guy is.

Rashi says that Ephron responded to Abraham by saying:

“Between two such friends as we are, of what importance is that? Nothing at all! Leave business alone and bury your dead!”

What friendship! Of course, go and do what you need to do, Ephron says.

On the other hand, Rashi also says Ephron isn’t that great when they were measuring out the payment:

And Abraham weighed to Ephron [the silver] — [The name Ephron is written] without the vav because [Ephron] said much, but even a little, he did not do.

Ephron talked a big game but didn’t really follow through.

Rashi gets this idea from the Talmud in Bava Metzia:

Rabbi Elazar said: From here we learn that the righteous say little and do much, whereas the wicked say much and do not do even a little. From where do we derive this principle that the wicked say much and do not do even a little? We derive it from Ephron.

So which is it? Are they generous buddies or is Ephron wicked? How does this help us with the idea of follow through?

Push through.

Abraham, in the midst of his grief, sought to find the right place to bury his wife. He knew, in his heart, that it was something he needed to for himself, a place that could be his without question.

When given the opportunity to take the land for free, he followed through with his principles. He did what he needed to do to finish the task, despite the profound challenges of grief and communal pressure.

Talk is cheap. Follow through matters.

By placing these two Rashi texts together, we get a picture of a “friend” who cares deeply and is there to provide help in a sad moment. But, perhaps he wasn’t really all that generous.

Tzilla Eshel, of Haifa University, wrote on TheTorah.com, a website “for Torah study informed by academic scholarship” on a piece about the value of silver in the ancient world. (Bolding mine)

Insofar as the price, 400 shekels was a possible/ realistic price in real estate transactions in Late Bronze Age Ugarit (Steiglitz 1979), although we cannot evaluate if it was a fair price for the specific land offered. It is equal to four and a half kilograms (a Judean shekel is valued as 11.33 grams), or around 10 pounds of silver.

According to documents we have from Ugarit, 400 shekels was not an outrageous price for land, but certainly not cheap either. Assuming 0.5 grams of silver would be a day laborer’s wage, if we translate this into modern terms, with an average day laborer’s wage being about $120, the price of land would be around $624,000—pricey, but manageable for a wealthy person like Abraham. To paraphrase Ephron, “what is six hundred thousand dollars and change between friends?”

Namely, Ephron talked about being understanding and generous, but when it was time to help his friend he didn’t really give his “buddy” a deal. He didn’t really follow through as a friend. One could say that he took advantage. This is what Rashi could mean when he says, “he talked a lot but did not do even a little.”

Say little, do much.

Our actions matter. What we do makes a difference. At a certain point, our words become meaningless if we don’t follow through.

Our favorite naysayer, Shammai, Rabbi Hillel’s foil is quoted in Pirkei Avot:

Shammai says, “Make your Torah [study] fixed, say little and do much, and receive every person with a pleasant countenance.”

We actually have to do the work at some point. We can’t just talk.

He also says we should smile more, but I’m not sure that helps us here.

So what do we do now?

I think we can take this moment, in Sarah’s memory, if you will, and think about how we can show up, face the challenges before us, be a good friend, push through and follow through.

The world needs us to do it. The world needs us to cross that threshold moment, to make the decision to the right thing, the moral thing, the kind thing, the scary thing.