October 8, 2020

When I vote, I vote with this in mind.

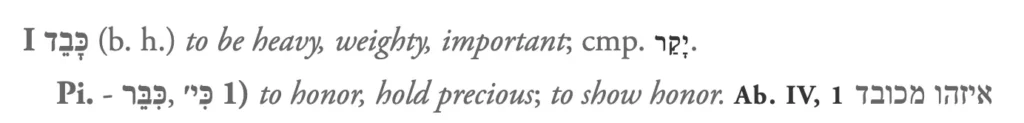

Over the course of this season, I’ve been thinking a lot about כּבוד, kavod. It comes from the root כבד, KVD, containing a sense of heaviness and importance, as you can see here, from the Jastrow dictionary:

You might recognize this word from a number of regular uses. To say, “good job!”, we might say, kol hakavod, “all of the honor [goes to you].” In conversation, people might say, b’khavod, “with respect.” Many folks will introduce a comment to their rabbi with the phrase, l’khvod harav, “to respect of the rabbi.”

B’khavod is a phrase I wish was a part of common American English so that I could use it more often. But, alas, it isn’t…yet.

In addition to the sense of literal heaviness, there are really two primary ways that this word interacts with our conceptions of reality: first, when we describe the Divine, and second, when we talk about honor and dignity.

In the context of Sukkot, the Torah describes God’s presence while sheltering the people as ענני הכבוד, an’nei hakavod, clouds of glory. As we might notice, we don’t really translate it has clouds of honor, but rather kavod as a concentrated form that we call glory. I’ll admit, I’m not entirely sure what glory really means, what it looks like, what it does. This also appears in the form of כסא הכבוד, kis’e hakavod, the throne of glory. If you look at the first chapter of the book of Ezekiel, this is what it’s describing.

In fact, Rashi tells us that

“[Sukkot in the Torah] does not mean literally “booths” but, “the clouds of Glory” by which they were sheltered.”

Kavod itself has the power of protection.

And then we have the definition of kavod as honor or dignity. It says in the Talmud, in Masechet Berachot:

תָּא שְׁמַע: גָּדוֹל כְּבוֹד הַבְּרִיּוֹת שֶׁדּוֹחֶה [אֶת] לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה

“Come and hear: Great is human dignity, as it overrides a prohibition in the Torah.”

The text is so fundamentally clear. Kavod haBriyot, the dignity of humans and living creatures will push aside a prohibition. It is hard to imagine a stronger statement.

What is human dignity?

Well, in Pirkei Avot, we’re told:

אֵיזֶהוּ מְכֻבָּד, הַמְכַבֵּד אֶת הַבְּרִיּוֹת, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (שמואל א ב) כִּי מְכַבְּדַי אֲכַבֵּד וּבֹזַי יֵקָלּוּ

“Who is the one that is honored? The one who honors their fellow human beings as it is said: “For I honor those that honor Me, but those who spurn Me shall be dishonored” (I Samuel 2:30).”

Honor and dignity are relational.

Human dignity is something that we enact with one another. The term we use for that kind of dynamic is bein adam l’chavero, between humans and their fellow.

Grounding this idea is the concept of b’tzelem elohim, the idea that humans are made in the image of the divine. One of my favorite texts, which appears in the context of Yom Kippur is this one, from Masechet Sanhedrin:

“The mishnah cites another reason Adam the first man was created alone: And this was done due to the importance of maintaining peace among people, so that one person will not say to another: My father, i.e., progenitor, is greater than your father.”

Human dignity is based on the idea that each of us has inherent value. That each of us, without distinction, is worthy and deserving of kavod haBriyot, honor and dignity.

Now the Tradition also has another term like this: kavod haTzibbur, the honor of the community. This term is complicated.

In the past, this has used to exclude people from participating in Jewish life. It is used to exclude women from leading or counting in a minyan for many centuries. The idea is that it would dishonor the community to include them.

This, to me, does exactly the opposite.

A community cannot be whole if the inclusion of others is a dishonor.

This is exactly what Rabbi Pamela Barmash corrects in her exceptional teshuvah, Women and Mitzvot. She writes:

“In reality, the social standing of women caused their exemption: the essential ritual acts are to be fulfilled by those of the highest social standing. Only they honor God in the most fitting way; only they uphold the dignity of the community…What women could not do was to be involved in public ritual acts and fulfill mitzvot on behalf of men. This impediment was due to their subordinate social status.

The role of women in public life has changed dramatically in modernity. In society in general, women are now involved in commerce and the professions on an equal basis with men, and secular law considers women legally free and independent. In Jewish communities, women have been seeking to enrich their lives with more mitzvot. The changes in women’s social lives in general and in Jewish communities are not just a matter of external behavior but reflect a changed perception of women. Women are now seen as equal to men in social status, in intellectual ability, and in political and legal rights. The historical circumstances in which women were exempted from certain mitzvot are no longer operative, and we must embrace the realities of life in the 21st century.”

In short, the status of women has changed. Therefore, to put it in the language we were using before, women, and previously marginalized groups, do not dishonor our communities, but instead, add to the honor.

As such, I’d like to add a few more kavod concepts to our lexicon and how we enact them.

(These, nor the examples, are exhaustive. I’d love to hear yours in the comments.)

Kavod HaAdam and Kavod haBriyot

The dignity of human beings and living creatures

This is our obligation to treat each other as inherently valuable. No one has to earn dignity. We act on this by recognizing immigrants to be just as human as we are. We do this by not referring to Trans folks by their deadname and by using their desired pronouns.

Kavod haGuf

The dignity of the body

This is our obligation to allow people to have autonomy over their own body. We honor one another’s dignity by respecting their physical space and body. The right to choose is an essential element of kavod haGuf. No one should be able to deny another their ability to have an abortion, to do otherwise would be to deny the dignity they retain with their own body.

Kavod haAhavah

The dignity of love

This is our obligation to respect the heart of one another. Only God and ourselves know the inner reaches of the heart. To treat each other with the kavod haAhavah is to protect one another’s right to love and marry whom they wish. We live in a society in which marriage equality should be extended to every person, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender. No one should be able to be fired for who they love. This teshuvah written to permit gay marriage uses kavod haBriyot to make the same point.

Kavod haHolim

The dignity of the ill

This is our obligation to protect the health, mental, physical, and spiritual, of each other. Our society should live up to the idea that each of us deserves to receive the resources we need. Kavod haHolim is to recognize that all of us should have healthcare. It should not matter what job you have, how many taxes you pay, nor your legal immigration status. To treat each other with dignity is to provide for one another.

Kavod haTzibur

The dignity of the community

This is our obligation to live in a society that dignifies each of our lives as valuable. This requires us to strive for equity and justice. Our community has dignity when there is fairness and when each of us can reach our full potential. Taking apart systems of structural racism provides dignity and benefit to all of us. We honor our neighbors when we can all live in an equitable society.

These are core and basic obligations we have to each other. It is a major task for our society to reach these aspirations. But for me, the central tenet of human dignity grounds me, inspires me, and encourages me.

Each moment and each act we take is an opportunity to invest in the kavod of our friends, our families, our neighbors, and the strangers we encounter.